Recent Posts

Think you know about deliverability?

- laura

- Sep 23, 2014

Check out the tweets from my AMA webinar sponsored by Message Systems today.

Thanks to the AMA and Message Systems for having me.

Reminder: AMA webinar

- laura

- Sep 22, 2014

Today is the last day to sign up for the AMA webinar hosted by MessageSystems and listen to me talk about the future of deliverability.

I hope to see you there!

Alice and Bob Sign Messages

- steve

- Sep 19, 2014

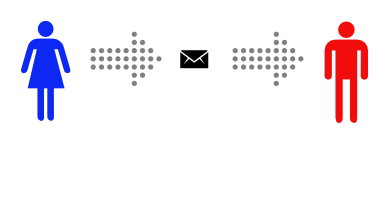

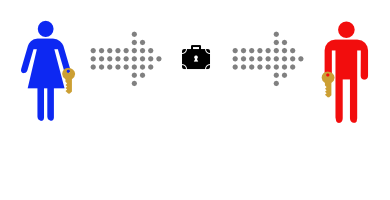

Alice and Bob can send messages privately via a nosy postman, but how does Bob know that a message he receives is really from Alice, rather than from the postman pretending to be Alice?

If they’re using symmetric-key encryption, and Bob is sure that he was talking to Alice when they exchanged keys, then he already knows that the mail is from Alice – as only he and Alice have the keys that are used to encrypt and decrypt messages, so if Bob can decrypt the message, he knows that either he or Alice encrypted it. But that’s not always possible, especially if Alice and Bob haven’t met.

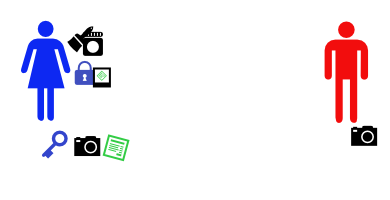

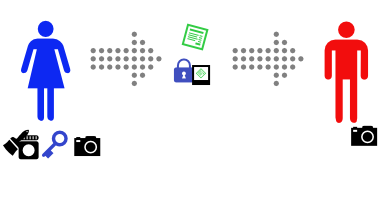

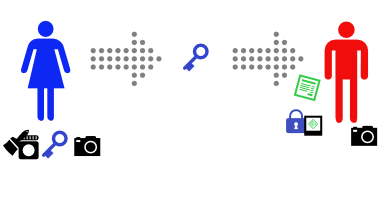

Alice’s shopping list is longer for signing messages than for encrypting them (and the cryptography to real world metaphors more strained). She buys some identical keys, and matching padlocks, some glue and a camera. The camera isn’t a great camera – funhouse mirror lens, bad instagram filters, 1970s era polaroid film – so if you take a photo of a message you can’t read the message from the photo. Bob also buys an identical camera.

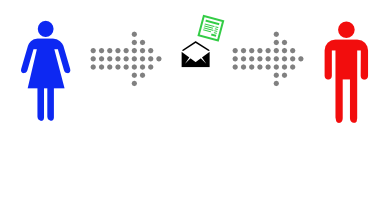

Alice takes a photo of the message.

Then Alice glues the photo to one of her padlocks.

Alice sends the message, and the padlock-glued-to-photo to Bob.

Bob sees that the message claims to come from Alice, so he asks Alice for her key.

(If you’re paying attention, you’ll see a problem with this step…)

Bob uses Alice’s key to open the padlock. It opens (and, to keep things simple, breaks).

Bob then takes a photo of the message with his camera, and compares it with the one glued to the padlock. It’s identical.

Because Alice’s key opens the padlock, Bob knows that the padlock came from Alice. Because the photo is attached to the padlock, he knows that the attached photo came from Alice. And because the photo Bob took of the message is identical to the attached photo, Bob knows that the message came from Alice.

This is how real world public-key authentication is often done.

Who's publishing DMARC?

- steve

- Sep 18, 2014

DMARC is a way for a domain owner to say “If you see this domain in a From: header and it’s not been sent straight from us, please don’t deliver the mail”. If a domain is only used for bulk and transactional mail, it can mitigate a subset of phishing attacks without causing too many problems for legitimate email.

In other cases, it can cause significant problems. Some of those problems impact discussion lists, but others cause problems for ESPs servicing small companies and individuals. ESP customers use their email addresses in the From: field; if they’re a small customer using the email address provided by their ISP, and that ISP publishes a DMARC record with p=reject, a large chunk of the mail they’re sending will bounce. When that happens recipients will stop getting their email, they’ll be removed from the mailing list due to bounces, and there’s some risk of blocks being raised against the sending IP address.

Because of that, it’s good to be able to see what consumer ISPs are doing with DMARC.

I’ve created a tool at dmarc.wordtothewise.com that regularly checks a list of large consumer ISPs and webmail providers and sees what DMARC records they’re publishing.

There are two main variants of DMARC records.

One is policy “reject” – meaning that mail that isn’t authenticated (or for which authentication has been broken in transit) will likely be rejected.

The other is policy “none” – meaning that the ISP publishing the record doesn’t want recipients to change their delivery decisions, but are asking for feedback about their mailstream, and how much of it fails authentication. That can mean that the ISP is evaluating whether or not to publish p=REJECT, or is in the process of deploying p=REJECT. Or it can just mean that they’re using DMARC to monitor where mail using their domain in the From: address is being sent from. There’s no way to tell which is the case unless they’ve made an announcement about their plans.

Hopefully this will be a useful tool to monitor DMARC deployment by consumer ISPs, and to help diagnose delivery problems that may be caused by DMARC.

Cryptography with Alice and Bob

- steve

- Sep 17, 2014

Untrusted Communication Channels

This is a story about Alice and Bob.

Alice wants to send a private message to Bob, and the only easy way they have to communicate is via postal mail.

Unfortunately, Alice is pretty sure that the postman is reading the mail she sends.

That makes Alice sad, so she decides to find a way to send messages to Bob without anyone else being able to read them.

Symmetric-Key Encryption

Alice decides to put the message inside a lockbox, then mail the box to Bob. She buys a lockbox and two identical keys to open it. But then she realizes she can’t send the key to open the box to Bob via mail, as the mailman might open that package and take a copy of the key.

Instead, Alice arranges to meet Bob at a nearby bar to give him one of the keys. It’s inconvenient, but she only has to do it once.

After Alice gets home she uses her key to lock her message into the lockbox. Then she sends the lockbox to Bob. The mailman could look at the outside, or even throw the box away so Bob doesn’t get the message – but there’s no way he can read the message, as he has no way of opening the lockbox.

Then she sends the lockbox to Bob. The mailman could look at the outside, or even throw the box away so Bob doesn’t get the message – but there’s no way he can read the message, as he has no way of opening the lockbox.

Bob can use his identical key to unlock the lockbox and read the message.

This works well, and now that Alice and Bob have identical keys Bob can use the same method to securely reply.

Meeting at a bar to exchange keys is inconvenient, though. It gets even more inconvenient when Alice and Bob are on opposite sides of an ocean.

Public-Key Encryption

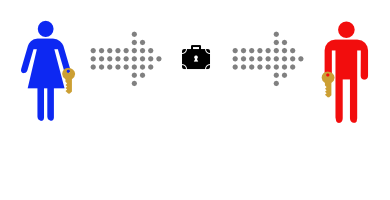

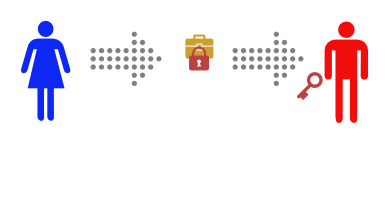

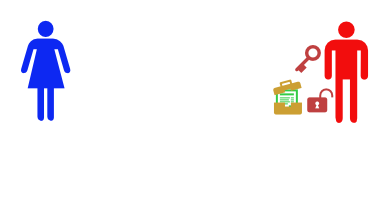

This time, Alice and Bob don’t ever need to meet. First Bob buys a padlock and matching key.

Then Bob mails the (unlocked) padlock to Alice, keeping the key safe.

Alice buys a simple lockbox that closes with a padlock, and puts her message in it.

Then she locks it with Bob’s padlock, and mails it to Bob.

She knows that the mailman can’t read the message, as he has no way of opening the padlock. When Bob receives the lockbox he can open it with his key, and read the message.

This only works to send messages in one direction, but Alice could buy a blue padlock and key and mail the padlock to Bob so that he can reply.

Or, instead of sending a message in the padlock-secured lockbox, Alice could send Bob one of a pair of identical keys.

Then Alice and Bob can send messages back and forth in their symmetric-key lockbox, as they did in the first example.

This is how real world public-key encryption is often done.

Cryptography and Email

- steve

- Sep 16, 2014

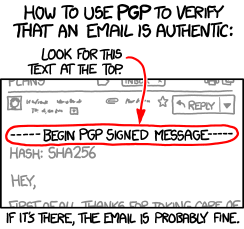

A decade or so ago it was fairly rare for cryptography and email technology to intersect – there was S/MIME (which I’ve seen described as having “more implementations than users”) and PGP, which was mostly known for adding inscrutable blocks of text to mail and for some interesting political fallout, but not much else.

That’s changing, though. Authentication and privacy have been the focus of much of the development around email for the past few years, and cryptography, specifically public-key cryptography, is the tool of choice.

DKIM uses public-key cryptography to let the author (or their ESP, or anyone else) attach their identity to the message in a way that’s almost impossible to forge. That lets the recipient make informed decisions about whether to deliver the email or not.

DKIM relies on DNS to distribute it’s public keys, so if you can interfere with DNS, you can compromise DKIM. More than that, if you can compromise DNS you can break many security processes – interfering with DNS is an early part of many attacks. DNSSEC (Domain Name System Security Extensions) lets you be more confident that the results you get back from a DNS query are valid. It’s all based on public-key cryptography. It’s taken a long time to deploy, but is gaining steam.

TLS has escaped from the web, and is used in several places in email. For end users it protects their email (and their passwords) as they send mail via their smarthost or fetch it from their IMAP server. More recently, though, it’s begun to be used “opportunistically” to protect mail as it travels between servers – more than half of the mail gmail sees is protected in transit. Again, public-key cryptography. Perhaps you don’t care about the privacy of the mail you’re sending, but the recipient ISP may. Google already give better search ranking for web pages served over TLS – I wouldn’t be surprised if they started to give preferential treatment to email delivered via TLS.

The IETF is beginning to discuss end-to-end encryption of mail, to protect mail against interception and traffic analysis. I’m not sure exactly where it’s going to end up, but I’m sure the end product will be cobbled together using, yes, public-key cryptography. There are existing approaches that work, such as S/MIME and PGP, but they’re fairly user-hostile. Attempts to package them in a more user-friendly manner have mostly failed so far, sometimes spectacularly. (Hushmail sacrificed end-to-end security for user convenience, while Lavabit had similar problems and poor legal advice).

Not directly email-related, but after the flurry of ESP client account breaches a lot of people got very interested in two-factor authentication for their users. TOTP (Time-Based One-Time Passwords) – as implemented by SecureID and Google Authenticator, amongst many others – is the most commonly used method. It’s based on public-key cryptography. (And it’s reasonably easy to integrate into services you offer).

Lots of the other internet infrastructure you’re relying on (BGP, syn cookies, VPNs, IPsec, https, anything where the manual mentions “certificate” or “key” …) rely on cryptography to work reliably. Knowing a little about how cryptography works can help you understand all of this infrastructure and avoid problems with it. If you’re already a cryptography ninja none of this will be a surprise – but if you’re not, I’m going to try and explain some of the concepts tomorrow.

Talking about deliverability

- laura

- Sep 16, 2014

Next Tuesday, September 23, I’ll be speaking about deliverability at a webinar sponsored by Message Systems and presented by the American Marketing Association.

Registration is open to all, so if you’re interested in hearing some of my opinions about deliverability past, present and future, sign up.

Dealing with compromised user accounts

- laura

- Sep 10, 2014

M3AAWG is on a roll lately with published documents. They recently released the Compromised User ID Best Practices (pdf link).

Read MoreContent based filtering

- laura

- Sep 10, 2014

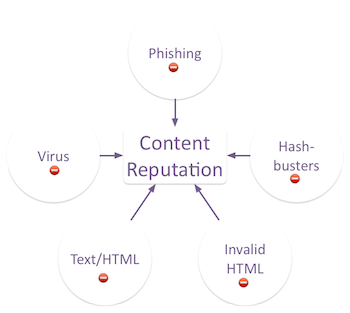

Content filtering is often hard to explain to people, and I’m not sure I’ve yet come up with a good way to explain it.

A lot of people think content reputation is about specific words in the message. The traditional content explanation is that words like “Free” or too many exclamation points in the subject line are bad and will be filtered. But it’s not the words that are the issue it’s that the words are often found in spam. These days filters are a lot smarter than to just look at individual words, they look at the overall context of the message.

Even when we’re talking content filters, the content is just a way to identify mail that might cause problems. Those problems are evaluated the same way IP reputation is measured: complaints, engagement, bad addresses. But there’s a lot more to content filtering than just the engagement piece. What else is part of content evaluation?

Categories

Tags

- 2010

- 2016

- 2fa

- 419

- 4xx

- 554

- 5xx

- @

- Aarp

- Abacus

- Abandoned

- Aboutmyemail

- Abuse

- Abuse Desk

- Abuse Enforcement

- Abuse Prevention

- Academia

- Accreditation

- Acme

- Acquisition

- Address Book

- Addresses

- Administrivia

- Adsp

- Advanced Delivery

- Advertiser

- Advertising

- Advice

- Affiliate

- Affiliates

- After the Email

- Alerts

- Algorithm

- Alice

- Alignment

- Allcaps

- Alt Text

- AMA

- Amazon

- Amp

- Amsterdam

- Analysis

- Anecdotes

- Anti-Spam

- Anti-Spam Laws

- Anti-Spammers

- Antwort

- AOL

- Appeals

- Appearances

- Appending

- Apple

- Arc

- Arf

- Arrest

- Arrests

- Ascii

- Asides

- Ask Laura

- Askwttw

- Assertion

- Assumptions

- ATT

- Attacks

- Attention

- Attrition

- Audit

- Authentication

- Authentication. BT

- Autonomous

- Award

- B2B

- B2C

- Backhoe

- Backscatter

- Backus-Naur Form

- Banks

- Barracuda

- Barry

- Base64

- Base85

- Bcc

- Bcp

- Bear

- Bears

- Behaviour

- Benchmark

- BESS

- Best Practices

- Bgp

- BIMI

- Bit Rot

- Bitly

- Bizanga

- Black Friday

- Blackfriday

- Blacklist

- Blacklists

- Blast

- Blo

- Block

- Blockin

- Blocking

- Blocklist

- Blocklisting

- Blocklists

- Blocks

- Blog

- Blog Links

- Blogroll

- Blogs

- Bob

- Boca

- Bofa

- Book Review

- Bot

- Botnet

- Botnets

- Bots

- Bounce

- Bounce Handling

- Bounces

- Branding

- Brands

- Breach

- Breaches

- Breech

- Bronto

- Browser

- Bsi

- Bucket

- Bulk

- Bulk Folder

- Bulk Mail

- Business

- Business Filters

- Buying Leads

- Buying Lists

- C-28

- CA

- Caa

- Cabbage

- Cache

- Cadence

- CAH

- California

- Campaign

- CAN SPAM

- Canada

- Candy

- Candycandycandy

- Canonicalization

- Canspam

- Captcha

- Career Developmnent

- Careers at WttW

- Cargo Cult

- Case Law

- Cases

- CASL

- Cat

- Cbl

- CDA

- Cert

- Certification

- CFL

- CFWS

- Change

- Charter

- Cheat

- Cheese

- Choicepoint

- Choochoo

- Christmas

- Chrome

- Cidr

- Cisco

- Civil

- Clear.net

- Clearwire.net

- Cli

- Click

- Click Through

- Click Tracking

- Clicks

- Clickthrough

- Client

- Cloudflare

- Cloudmark

- Cname

- Co-Reg

- Co-Registration

- Cocktail

- Code

- COI

- Comcast

- Comments

- Commercial

- Communication

- Community

- Comodo

- Comparison

- Competitor

- Complaint

- Complaint Rates

- Complaints

- Compliancce

- Compliance

- Compromise

- Conference

- Conferences

- Confirmation

- Confirmed (Double) Opt-In

- Confirmed Opt-In

- Congress

- Consent

- Conservatives

- Consistency

- Constant Contact

- Consultants

- Consulting

- Content

- Content Filters

- Contracts

- Cookie

- Cookie Monster

- COPL

- Corporate

- Cost

- Court Ruling

- Cox

- Cox.net

- Cpanel

- Crib

- Crime

- CRM

- Crowdsource

- Crtc

- Cryptography

- CSRIC

- CSS

- Curl

- Customer

- Cyber Monday

- Czar

- Data

- Data Hygiene

- Data Security

- Data Segmentation

- Data Verification

- DBL

- Dbp

- Ddos

- Dea

- Dead Addresses

- Dedicated

- Dedicated IPs

- Defamation

- Deferral

- Definitions

- Delays

- Delisting

- Deliverability

- Deliverability Experts

- Deliverability Improvement

- Deliverability Summit

- Deliverability Week

- Deliverability Week 2024

- Deliverabiltiy

- DeliverabiltyWeek

- Delivery Blog Carnival

- Delivery Discussion

- Delivery Emergency

- Delivery Experts

- Delivery Improvement

- Delivery Lore

- Delivery News

- Delivery Problems

- Dell

- Design

- Desks

- Dhs

- Diagnosis

- Diff

- Dig

- Direct Mag

- Direct Mail

- Directives

- Discounts

- Discovery

- Discussion Question

- Disposable

- Dk

- DKIM

- Dkimcore

- DMA

- DMARC

- DNS

- Dnsbl

- Dnssec

- Docs

- Doingitright

- Domain

- Domain Keys

- Domain Reputation

- DomainKeys

- Domains

- Domains by Proxy

- Dontpanic

- Dot Stuffing

- Dotcom

- Double Opt-In

- Dublin

- Dyn

- Dynamic Email

- E360

- Earthlink

- Ec2

- Ecoa

- Economics

- ECPA

- Edatasource

- Edns0

- Eec

- Efail

- Efax

- Eff

- Election

- Email Address

- Email Addresses

- Email Change of Address

- Email Client

- Email Design

- Email Formats

- Email Marketing

- Email Strategy

- Email Verification

- Emailappenders

- Emailgeeks

- Emails

- Emailstuff

- Emoji

- Emoticon

- Encert

- Encryption

- End User

- Endusers

- Enforcement

- Engagement

- Enhanced Status Code

- Ennui

- Entrust

- Eol

- EOP

- Epsilon

- Esp

- ESPC

- ESPs

- EU

- Ev Ssl

- Evaluating

- Events

- EWL

- Exchange

- Excite

- Expectations

- Experience

- Expires

- Expiring

- False Positives

- FAQ

- Fathers Day

- Fbl

- FBL Microsoft

- FBLs

- Fbox

- FCC

- Fcrdns

- Featured

- Fedex

- Feds

- Feedback

- Feedback Loop

- Feedback Loops

- Fiction

- Filter

- Filter Evasion

- Filtering

- Filterings

- Filters

- Fingerprinting

- Firefox3

- First Amendment

- FISA

- Flag Day

- Forensics

- Format

- Formatting

- Forms

- Forwarding

- Fraud

- Freddy

- Frequency

- Friday

- Friday Spam

- Friendly From

- From

- From Address

- FTC

- Fussp

- Gabbard

- GDPR

- Geoip

- Gevalia

- Gfi

- Git

- Giveaway

- Giving Up

- Global Delivery

- Glossary

- Glyph

- Gmail

- Gmails

- Go

- Godaddy

- Godzilla

- Good Email Practices

- Good Emails in the Wild

- Goodmail

- Google Buzz

- Google Postmaster Tools

- Graphic

- GreenArrow

- Greylisting

- Greymail

- Groupon

- GT&U

- Guarantee

- Guest Post

- Guide

- Habeas

- Hack

- Hacking

- Hacks

- Hall of Shame

- Harassment

- Hard Bounce

- Harvesting

- Harvey

- Hash

- Hashbusters

- Headers

- Heartbleed

- Hearts

- HELO

- Help

- Henet

- Highspeedinternet

- Hijack

- History

- Holiday

- Holidays

- Holomaxx

- Hostdns4u

- Hostile

- Hostname

- Hotmail

- How To

- Howto

- Hrc

- Hsts

- HTML

- HTML Email

- Http

- Huey

- Humanity

- Humor

- Humour

- Hygiene

- Hypertouch

- I18n

- ICANN

- Icloud

- IContact

- Identity

- Idiots

- Idn

- Ietf

- Image Blocking

- Images

- Imap

- Inbox

- Inbox Delivery

- Inboxing

- Index

- India

- Indiegogo

- Industry

- Infection

- Infographic

- Information

- Inky

- Inline

- Innovation

- Insight2015

- Integration

- Internationalization

- Internet

- Intuit

- IP

- IP Address

- Ip Addresses

- IP Repuation

- IP Reputation

- IPhone

- IPO

- IPv4

- IPv6

- Ironport

- Ironport Cisco

- ISIPP

- ISP

- ISPs

- J.D. Falk Award

- Jail

- Jaynes

- JD

- Jobs

- Json

- Junk

- Juno/Netzero/UOL

- Key Rotation

- Keybase

- Keynote

- Kickstarter

- Kraft

- Laposte

- Lavabit

- Law

- Laws

- Lawsuit

- Lawsuits

- Lawyer

- Layout

- Lead Gen

- Leak

- Leaking

- Leaks

- Legal

- Legality

- Legitimate Email Marketer

- Letsencrypt

- Letstalk

- Linked In

- Links

- List Hygiene

- List Management

- List Purchases

- List the World

- List Usage

- List-Unsubscribe

- Listing

- Listmus

- Lists

- Litmus

- Live

- Livingsocial

- London

- Lookup

- Lorem Ipsum

- Lycos

- Lyris

- M3AAWG

- Maawg

- MAAWG2007

- Maawg2008

- MAAWG2012

- MAAWGSF

- Machine Learning

- Magill

- Magilla

- Mail Chimp

- Mail Client

- MAIL FROM

- Mail Privacy Protection

- Mail Problems

- Mail.app

- Mail.ru

- Mailboxes

- Mailchimp

- Mailgun

- Mailing Lists

- Mailman

- Mailop

- Mainsleaze

- Maitai

- Malicious

- Malicious Mail

- Malware

- Mandrill

- Maps

- Marketer

- Marketers

- Marketing

- Marketo

- Markters

- Maths

- Mcafee

- Mccain

- Me@privacy.net

- Measurements

- Media

- Meh

- Meltdown

- Meme

- Mentor

- Merry

- Message-ID

- Messagelabs

- MessageSystems

- Meta

- Metric

- Metrics

- Micdrop

- Microsoft

- Milter

- Mime

- Minimal

- Minshare

- Minute

- Mit

- Mitm

- Mobile

- Models

- Monitoring

- Monkey

- Monthly Review

- Mpp

- MSN/Hotmail

- MSN/Hotmail

- MTA

- Mua

- Mutt

- Mx

- Myths

- Myvzw

- Needs Work

- Netcat

- Netsol

- Netsuite

- Network

- Networking

- New Year

- News

- News Articles

- Nhi

- NJABL

- Now Hiring

- NTP

- Nxdomain

- Oath

- Obituary

- Office 365

- Office365

- One-Click

- Only Influencers

- Oops

- Opaque Cookie

- Open

- Open Detection

- Open Rate

- Open Rates

- Open Relay

- Open Tracking

- Opendkim

- Opens

- Openssl

- Opt-In

- Opt-Out

- Optonline

- Oracle

- Outage

- Outages

- Outblaze

- Outlook

- Outlook.com

- Outrage

- Outreach

- Outsource

- Ownership

- Owning the Channel

- P=reject

- Pacer

- Pander

- Panel

- Password

- Patent

- Paypal

- PBL

- Penkava

- Permission

- Personalities

- Personalization

- Personalized

- Pgp

- Phi

- Philosophy

- Phish

- Phishers

- Phishing

- Phising

- Photos

- Pii

- PIPA

- PivotalVeracity

- Pix

- Pluscachange

- Podcast

- Policies

- Policy

- Political Mail

- Political Spam

- Politics

- Porn

- Port25 Blocking

- Postfix

- Postmaster

- Power MTA

- Practices

- Predictions

- Preferences

- Prefetch

- Preview

- Primers

- Privacy

- Privacy Policy

- Privacy Protection

- Private Relay

- Productive Mail

- Promotions

- Promotions Tab

- Proofpoint

- Prospect

- Prospecting

- Protocols

- Proxy

- Psa

- PTR

- Public Suffix List

- Purchased

- Purchased Lists

- Purchases

- Purchasing Lists

- Questions

- Quoted Printable

- Rakuten

- Ralsky

- Rant

- Rate Limiting

- Ray Tomlinson

- Rc4

- RDNS

- Re-Engagement

- Read

- Ready to Post

- Readytopost

- Real People

- Realtime Address Verification

- Recaptcha

- Received

- Receivers

- Recipient

- Recipients

- Redirect

- Redsnapper

- Reference

- Registrar

- Registration

- Rejection

- Rejections

- Rejective

- Relationship

- Relevance

- Relevancy

- Removals

- Render Rate

- Rendering

- Replay

- Repost

- Repudiation

- Reputation

- Requirements

- Research

- Resources

- Responsive

- Responsive Design

- Responsys

- Retail

- Retired Domains

- Retro

- Return Path

- Return Path Certified

- ReturnPath

- Reunion.com

- Reverse Dns

- RFC

- RFC2047

- RFC2821/2822

- RFC5321/5322

- RFC5322

- RFC8058

- RFC821/822

- RFCs

- Roadr

- RoadRunner

- Rodney Joffe

- ROKSO

- Role Accounts

- Rollout

- RPost

- RPZ

- Rule 34

- Rules

- Rum

- Rustock

- S.1618

- SaaS

- Sales

- Salesforce

- Sass

- SBCGlobal

- Sbl

- Scam

- Scammers

- Scams

- Scanning

- Scraping

- Screamer

- Screening

- Script

- Sec

- Secure

- Security

- Segmentation

- Selligent

- Send

- Sender

- Sender Score

- Sender Score Certified

- Senderbase

- Senderid

- Senders

- Senderscore

- Sendgrid

- Sending

- Sendy

- Seo

- Service

- Services

- Ses

- Seth Godin

- SFDC

- SFMAAWG2009

- SFMAAWG2010

- SFMAAWG2014

- Shared

- Shell

- Shouting

- Shovel

- Signing

- Signups

- Silly

- Single Opt-In

- Slack

- Slicing

- Smarthost

- Smiley

- Smime

- SMS

- SMTP

- Snds

- Snowshoe

- Soa

- Socia

- Social Media

- Social Networking

- Soft Bounce

- Software

- Sony

- SOPA

- Sorbs

- Spam

- Spam Blocking

- Spam Definition

- Spam Filtering

- Spam Filters

- Spam Folder

- Spam Law

- Spam Laws

- Spam Reports

- Spam Traps

- Spam. IMessage

- Spamarrest

- Spamassassin

- Spamblocking

- Spamcannibal

- Spamcon

- Spamcop

- Spamfiltering

- Spamfilters

- Spamfolder

- Spamhaus

- Spamhause

- Spammer

- Spammers

- Spammest

- Spamming

- Spamneverstops

- Spamresource

- Spamtrap

- Spamtraps

- Spamza

- Sparkpost

- Speaking

- Special Offers

- Spectre

- SPF

- Spoofing

- SproutDNS

- Ssl

- Standards

- Stanford

- Starttls

- Startup

- State Spam Laws

- Statistics

- Storm

- Strategy

- Stunt

- Subject

- Subject Lines

- Subscribe

- Subscriber

- Subscribers

- Subscription

- Subscription Process

- Success Stories

- Suing

- Suppression

- Surbl

- Sureclick

- Suretymail

- Survey

- Swaks

- Syle

- Symantec

- Tabbed Inbox

- Tabs

- Tagged

- Tagging

- Target

- Targeting

- Techincal

- Technical

- Telnet

- Template

- Tempo

- Temporary

- Temporary Failures

- Terminology

- Testing

- Text

- Thanks

- This Is Spam

- Throttling

- Time

- Timely

- TINS

- TLD

- Tlp

- TLS

- TMIE

- Tmobile

- Too Much Mail

- Tool

- Tools

- Toomuchemail

- Tor

- Trademark

- Traffic Light Protocol

- Tragedy of the Commons

- Transactional

- Transition

- Transparency

- Traps

- Travel

- Trend/MAPS

- Trend Micro

- Trend/MAPS

- Trigger

- Triggered

- Troubleshooting

- Trustedsource

- TWSD

- Txt

- Types of Email

- Typo

- Uce

- UCEprotect

- Unblocking

- Uncategorized

- Undisclosed Recipients

- Unexpected Email

- Unicode

- Unroll.me

- Unsolicited

- Unsubcribe

- Unsubscribe

- Unsubscribed

- Unsubscribes

- Unsubscribing

- Unsubscription

- Unwanted

- URIBL

- Url

- Url Shorteners

- Usenet

- User Education

- Utf8

- Valentine's Day

- Validation

- Validity

- Value

- Valueclick

- Verification

- Verizon

- Verizon Media

- VERP

- Verticalresponse

- Vetting

- Via

- Video

- Violence

- Virginia

- Virtumundo

- Virus

- Viruses

- Vmc

- Vocabulary

- Vodafone

- Volume

- Vzbv

- Wanted Mail

- Warmup

- Weasel

- Webinar

- Webmail

- Weekend Effect

- Welcome Emails

- White Space

- Whitelisting

- Whois

- Wiki

- Wildcard

- Wireless

- Wiretapping

- Wisewednesday

- Women of Email

- Woof

- Woot

- Wow

- Wtf

- Wttw in the Wild

- Xbl

- Xfinity

- Xkcd

- Yahoo

- Yahoogle

- Yogurt

- Zoidberg

- Zombie

- Zombies

- Zoominfo

- Zurb