Recycled addresses, spamtraps and sensors

A few hours ago I was reading an ESP blog post that recommended removing addresses after they were inactive for a year because the address could turn into a spamtrap. That is not how addresses turn into spamtraps and not why we want to remove active addresses. Moreover, it demonstrates a deep misunderstanding of spamtraps. Unfortunately, there are a lot of myths and misunderstandings of spamtraps in general.

The wrongness here is that any company doing even a half-assed job at bounce handling isn’t going to suddenly discover they’re mailing spamtraps. Yes, some ISPs have, in the past, turned abandoned addresses into spamtraps. Hotmail did it once back in the early 00’s. After that, it became common knowledge that all the mail providers were recycling addresses on a regular basis. Of course, the providers weren’t going to correct this, because it actually had the effect of many mailers being better citizens.

The reality is recycled addresses aren’t a major part of ISP filtering schemes these days. Recycling address into spamtraps takes work and a lot of time. At a bare minimum addresses must bounce for 12 months. Then they can start receiving mail again, but the mail must be examined to see what is valid and what is invalid mail. One cable provider I spoke with back in 2009 had employees unsubscribing from legitimate looking mail as part of their trap conditioning process. This provider eventually decided that the data wasn’t good enough to justify the work and gave up trying to use recycled traps.

I spend a lot of much time and energy talking about traps, removing traps, fixing the “spamtrap problem.” I can’t count the number of times I’ve been asked by an ESP, “How many pristine spamtrap hits should we allow before we cut off the customer? 3? 5? 10? What about recycled traps?” This all relates to the data from sensor networks multiple companies are providing. To be fair, public documents from both companies don’t call their sensor networks spamtraps. But every sender I know who has access to the data calls them spamtraps.

It frustrates me to no end because I know that these ESPs are really trying to do the best they can with the data they have. And having access to sensor network data is so appealing. They feel like a magic bullet to determining which customers are good and which customers are bad. But when we’re talking about sensor networks, we’re talking about addresses that would simply have hard bounced a few years ago. If you’re going to cut a customer off for hitting 3 or 5 or 10 pristine trap hits from one of the sensor networks, then you should also cut customers off for attempting to send mail to any non-existent domain. There Is No Difference.

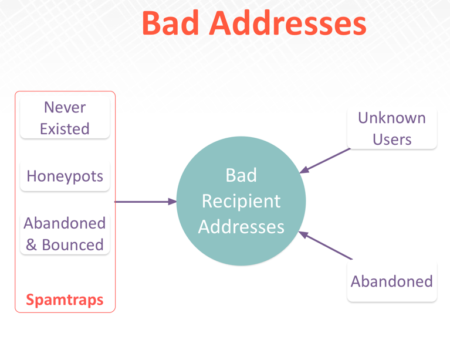

This isn’t a new belief of mine. Back in 2014 I was using a presentation deck with this slide:

It’s even more true now that any abandoned domain can be part of a sensor network. Every address on a list that is not deliverable should be treated the same

What does all this mean? It means we need to rethink how we’re monitoring customers and email addresses. Lines are getting blurry and the difference between a spamtrap and a NXDomain or unknown address is all in who owns the address.

Other WttW Spamtrap Posts:

- Only spamtraps matter, or do they?

- Spamtraps, again.

- Spamtraps are not the problem

- Spamtraps mean your list is bad

- Spamtraps: should you care?

- A brief guide to spamtraps (I can’t believe this is over 8 years old)

- Typo traps

- The true facts of spam traps and typo traps

- More on spamtraps

- We only mail people who sign up!

- What about the spamtraps?