Fun with spam filters

I recently had a challenging travel experience in the Netherlands, trying to get from Schipol airport to a conference I was speaking at. As part of my attempt to get out of the airport, I installed UBER on my phone. There were some challenges with getting UBER to authorise my phone number, so I tried linking it to my Gmail account.

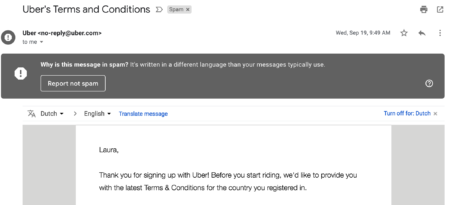

I checked Gmail today and noticed there was a message from UBER sitting in my spam folder. Why? Because the language of the email was “a different language than [my] messages usually use.”

Language filters are ones we don’t often talk about. I will sometimes mention them when I’m discussing the scope of what filters look like. But for most senders, they’re never going to send a message that is in a language different than the default language of the user. The confluence of events that caused me to sign up for UBER in a non-English-speaking country was somewhat unique.

At the time I signed up for UBER I was in The Netherlands. So, appropriately, they sent me the terms and conditions that cover riders there. They sent said terms and conditions to me in Dutch, because that’s the default language in the country where I activated my account. I wonder, though, if I had signed up with my Irish (or even US) phone number rather than my Gmail account, if the message would have arrived in English. Of course, being back in an English speaking country, it’s hard to test.

One thing this does tell me is “not in users’ primary language” is a huge negative in Gmail. This is UBER. When it comes to email they do things right.

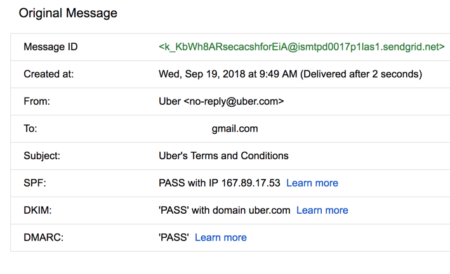

Authentication is spot on. Gmail KNOWS this message is really from UBER. DKIM checks out, it’s aligned with the From: address, there’s a DMARC record. The content is UBERs terms and conditions, and I’m sure Google knows that, too. As UBERs service continues to grow, I’m sure this content is sent regularly and at a high enough volume to generate a strong positive reputation. Google even knows it was me that signed up for UBER because I used Google’s OAUTH to connect UBER to my gmail address.

Still, none of that was enough to get Google to deliver the mail to my inbox. It’s not my language, so it goes to bulk. I’m sure, though, that all the native Dutch speakers got the exact same message in their inbox.

It’s rare we can see how one single factor can so clearly affect delivery of an otherwise good, high reputation stream. But, as I regularly say: context matters. In this case, a different language matters more than any positive reputation signals, including the fact that I signed up using my Google account.

Filtering at some places is more complex than spam or not spam. It’s about what the user wants and expects in their inbox. Send something the webmail provider thinks is not what the user wants or expects, and mail is likely to end up in the bulk folder.