Collecting email addresses

- laura

- January 26, 2018

- Best practices

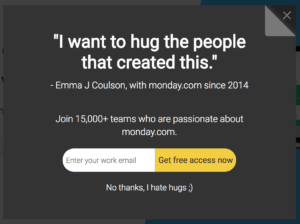

One of the primary ways to collect email addresses is from website visitors, and it’s actually a pretty good way to collect addresses. One of the more popular, and effective, techniques is through a pop-up window, asking for an address. Users need to provide an address or click a “no thanks” link or close the window. I’ve noticed, though, that many companies drop something passive aggressive in their “no thanks” button. “No, thanks, I don’t want to save money.” “I don’t need workout advice.”

Of course, I’m not the only one who’s noticed. Many people have commented on this phenomenon. I’ve heard it called confirmshaming and the Nielsen Norman Group called them manipulinks. Someone even started a tumblr for screenshots of the ways companies try to manipulate visitors into handing over their email address.

In deliverability terms, I don’t think this is a great strategy. Manipulating users into giving you an email address is never a good thing for finding enthusiastic engaged users. I’ve written before about how some opt-in schemes are closer to taking permission asking for it. Confirm shaming is not exactly taking permission, but it is senders attempting to get an email address from a user who might not otherwise be inclined to share personal information.

Interestingly enough, there is some small amount of research showing that these techniques, despite showing an increase in address acquisition, may drive down brand reputation.

Although manipulinks may in fact cause people to pause, consider, and even convert in higher numbers, there’s a hidden tradeoff involved. This approach will negatively impact your user’s experience in ways that aren’t as easily quantified with A/B testing. The short-term gains seen by increased micro conversions will come at the expense of disrespecting users, which will likely result in long term losses. Are a few more newsletter signups worth lower NPS scores? Or a negative brand perception? Or a loss of credibility and users’ trust?

[…] When companies use dirty tactics like this and then see conversion increases, it probably has less to do with “clever” manipulink text than with the fact that they’re straight up lying to their users. And that’s not just a needy pattern, it’s a dark pattern. Stop Shaming Your Users for Micro Conversions

The article didn’t discuss deliverability related to collecting addresses through manipulinks. I’m not sure anyone has. But if these links contribute to a negative user experience on the website, it’s likely the negative feelings transfer to the emails. Even if the emails themselves are great and don’t continue the negative user experience, how engaged are these users? Do companies using manipulinks to collect email addresses see any difference in deliverability from companies that don’t?

Major webmail providers focus on user experience. We know address collection processes are and important factor in reaching the inbox. Starting off an email relationship by shaming could hurt inboxing. Anyone have data?

Edit: Brian points out that Google is already watching who is doing full overlays and downgrading sites based on the overlays.