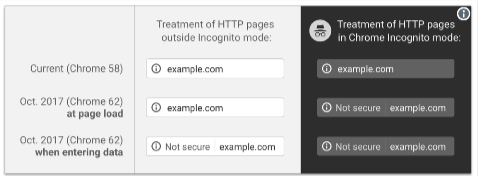

Transport Layer Security (TLS) is what gives you the little padlock in your browser bar. Some people still call it SSL, but TLS has been around for 18 years – it’s time to move on.

TLS provides two things. One is encryption of traffic as it goes across the wire, the other is a cryptographic proof that you’re talking to the domain you think you’re talking to.

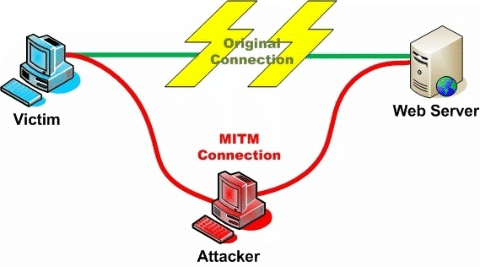

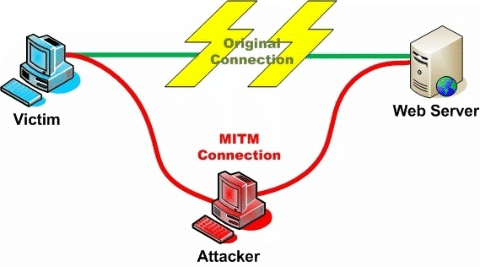

The second bit is important, as if you can’t prove you’re talking to, for example, your bank you could really be talking to a malicious third party who has convinced your browser to talk to their server instead of your bank which makes the encryption of the traffic much less useful. They could even act as a man-in-the-middle and pass your traffic through to your bank, so that you wouldn’t notice anything wrong.

When your browser connects to a website over TLS it, as part of setting up the connection, fetches a “TLS certificate” from the server. That certificate includes the hostname of the server, so the browser can be sure that it’s talking to the server it thinks it is.

How does the browser know to trust the certificate, though? There’s not really a great way to do that, yet. There’s a protocol called DANE that stores information in DNS to validate the certificate, much the same as we do with DKIM. It’s a promising approach, but not widely supported.

What we have today are “Certificate Authorities” (CAs). These are companies that will confirm that you own a domain, issue you a certificate for that domain where they vouch for it’s authenticity (and usually charge you for the privilege). Anyone can set themselves up as a CA (really – it’s pretty trivial, and you can download scripts to do the hard stuff), but web browsers keep a list of “trusted” CAs, and only certificates from those authorities count. Checking my mac, I see 169 trusted root certificate authorities in the pre-installed list. Many of those root certificates “cross-sign” with other certificate authorities, so the actual number of companies who are trusted to issue TLS Certificates is much, much higher.

If any of those trusted CAs issue a certificate for your domain name to someone, they can pretend to be you, secure connection padlock and all.

Some of those trusted CAs are trustworthy, honest and competent. Others aren’t. If a CA is persistently, provably dishonest enough then they may, eventually, be removed from the list of trusted Certificate Authorities, as StartCom and WoSign were last year. More often, they don’t: Trustwave, MCS Holdings/CNNIC, ANSSI, National Informatics Center of India (who are currently operating a large spam operation, so …).

In 2011 attackers compromised a Dutch CA, DigiNotar, and issued themselves TLS Certificates for over 500 high-profile domains – Skype, Mozilla, Microsoft, Gmail, … – and used them as part of man-in-the-middle attacks to compromise hundreds of thousands of users in Iran. Coverage at the time blamed it on “DigiNotar’s shocking ineptness“.

In 2015 Symantec/Thawte issued 30,000 certificates without authorization of the domain owners, and even when they issued extended validation (“green bar”) certificates for “google.com” they weren’t removed from the trusted list.

So many CAs are incompetent, many are dishonest, and any of them can issue a certificate for your domain. Even if you choose to use a competent, reputable CA – something that’s not trivial in itself – that doesn’t stop an attacker getting certificates for your domain from somewhere else.

This is where CAA DNS records come in. They’re really simple and easy to explain, with no fancy crypto needed to set them up. If I publish this DNS record …

Read More