Email pranks and spoofing

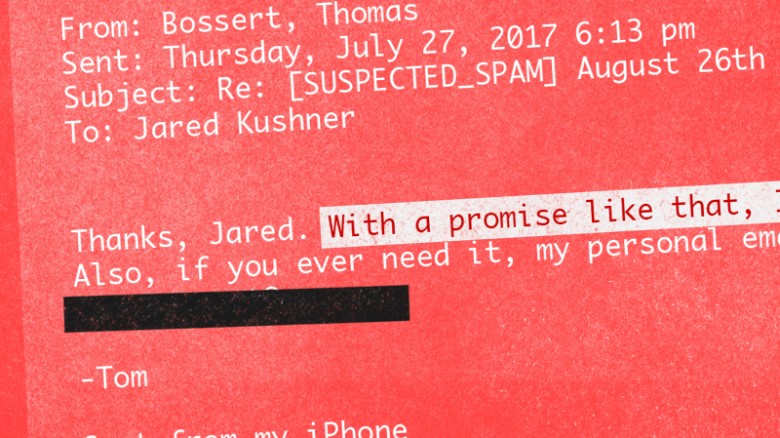

Earlier today a twitter user calling himself Email Prankster released copies of email conversations with various members of the current US administration. Based on his twitter feed, and articles from BBC News and CNN, it appears that the prankster forged “friendly from” names in emails to staffers.

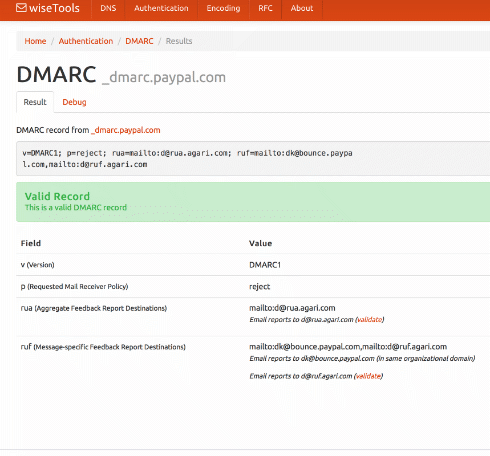

A bunch of folks will jump on this bandwagon and start making all sorts of claims about how this kind of thing would be prevented if the Whitehouse and other government offices would just implement DMARC. Problem is, that’s not true. It wouldn’t have helped at all in this case. Looking at the email screenshots all of the mail seems to come from legitimately registered addresses at free email providers like mail.com, gmail.com, and yandex.com.

One image indicates that some spam filter noticed there may be a problem. But apparently SUSPECTED_SPAM in the subject line wasn’t enough to make recipients think twice about checking the email.

The thing is, this is not “hacking” and this isn’t “spear phishing” and it’s not even really spoofing. It’s social engineering, at best. Maybe.

No, no masking the addresses I used. No 'hacking' either. I can barely operate our TV remote. Human behaviour and weakness was my weapon https://t.co/GDFoY0k7UF

— James Linton (@SINON_REBORN) August 1, 2017

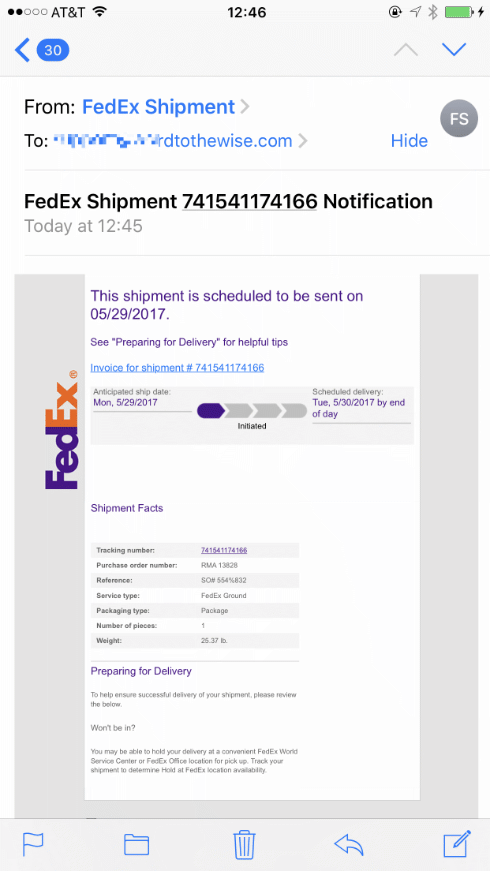

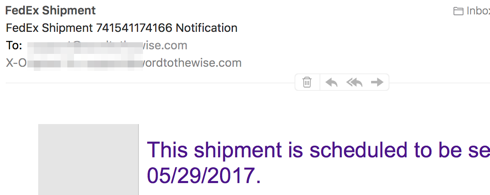

Modern mail clients make this kind of thing trivial. They often hide the email address from the user. Mobile mail clients are horrible about this. They often don’t even have the option to look at the actual email address. I regularly put clicking, opening or responding to an email on the back burner until I can get to my desk and see the full message. Often the message is fine. But sometimes it isn’t.

Email is a hostile channel. We, as users, need to treat it that way. I saw a discussion about this on Facebook earlier today. How can we, as the people who contribute to email standards, make it easier to identify spoofs like this? Well, as long as recipients are going to reply to arthur.schwartz@yandex.com or reince.priebus@mail.com as if they were from @whitehouse.gov we can’t. Even Eric Trump somewhat failed when he replied to “donaldtrumpjr.trump@gmail.com” asking if he really sent the email. (Don’t respond, create a new mail to the address you already have from him.)

This is just another example of how humans are the weakest link in any security scheme. Technology can help – maybe there should be a MUA tag that shows whether or not this is an email address (not name, email address) you’ve corresponded with before. But technology cannot save us from ourselves if we’re distracted or negligent.