Why is bounce handling so hard

- laura

- April 3, 2017

- Best practices

It should be easy, right? Except it’s not. So why is it so hard?

With one-on-one or one-to-few email it’s pretty simple. The rejections typically go back to a human who reads the text part of the rejection message and adapt and makes the decision about future messages. The software handles what to do with the undeliverable message based on the SMTP response code.

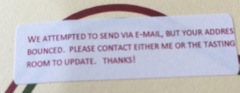

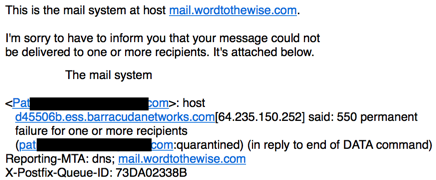

In the case of a 5xy response the server stops attempting delivery and alerts the original sender the mail failed. One example from helping a client troubleshoot a delivery problem recently.

There’s useful information in the text portion of this email from my mail server. It says there was a permanent failure (550) and that my message won’t be delivered. It also says the email is quarantined in reply to the end of DATA. That’s actually a critical piece of information. It means Barracuda saw the entire message before deciding to reject it. It’s likely a problem with the content of the email and so I need to look at links in the message.

This type of plain text explanation is great for a human to read and act on. But it’s not that simple for list handling software to identify the relevant information in the text message and act on future emails to that recipient. Different MTA vendors and ESPs have done a lot of work to try and correctly parse bounce messages to pull out relevant information.

ISPs have tried to help the situation by giving more descriptive rejection messages. They’re still using the SMTP required 3 digit numbers, but they include short, parseable codes in the text portion of the message. In many cases they also include URLs and links that open up webpages explaining the meaning of the code. They even post a list of the most common codes on their postmaster webpages.

All of these things make it somewhat easier to handle bounces automatically. Kinda.

I’ve been working on some bounce handling recommendations for a client using a few different ESPs. I spent a good few days digging into the bounces returned by their different ESPs. It was an interesting exercise as it demonstrated how very differently ESPs handle bounces. But it also clarified for me that there are a lot of different kinds of bounces.

- Address related bounces: user unknown, mailbox unavailable, invalid address, bad address syntax.

- Network related bounces: DNS failures, server too busy, temporarily unavailable, network error, connection timed out.

- Reputation related bounces: poor IP reputation, IP blocked, content blocked, too many complaints, prohibited attachment.

- Bad sending configuration: relaying denied, message too large,

- Authentication failure: DMARC

There’s also an overlap of Network and Reputation bounces: too many connections and too many messages are network methods to slow down sending of problematic mail.

None of these are always hard or always soft bounces. There are multiple ESPs that have also introduced the concept of “spam” bounce, which are an attempt to separate out some of the bounces due to problematic content from bounces labeled “hard” or “soft.”

I still hold out hope that someone, somewhere will come up with the grand unified theory of bounce handling. I suspect I’ll get a pony before that happens, though. I’m starting to get a better handle, though, on how to explain bounce handing – both in helping people visualize the different categories and clarifying what should be done with different messages.