The origins of network email

The history of long distance communication is a fascinating, and huge, subject. I’m going to focus just on the history of network email – otherwise I’m going to get distracted by AUTODIN and semaphore and facsimile and all sorts of other telegraphy.

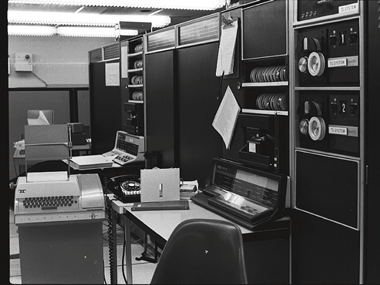

Electronic messaging between users on the same timesharing computer was developed fairly soon after time-sharing computer systems were available, beginning around 1965 – including both instant messaging and mail. I’m interested in network mail, though, so we need to skip forward a few years.

You need a network. And a community.

Around 1968 the initial plans for “ARPANET”, a network to link the various ARPA-funded computers together were underway. Local mail between users on the same system was already a significant part of the nascent community.

Q.What did you discover?

A. The thing that really struck me about this evolution was how these three systems caused communities to get built. People who didn’t know one another previously would now find themselves using the same system. Because the systems allowed you to share files, you could find that so-and-so was interested in such-and-such and he had some data about it. You could contact him by e-mail and, lo and behold, you would have a whole new relationship.

Q.Were these first communities built around mailing lists?

A. Well, you had a directory, so you knew how to send them e-mail, but you might only know 2 or 3 people, and you would meet 20 or 30 through the computer.

It wasn’t a static medium. It was a dynamic medium. And that gave it a lot of power.

Q.It was all about community?

A. There was one other trigger that turned me to the ARPAnet. For each of these three terminals, I had three different sets of user commands. So if I was talking online with someone at S.D.C. and I wanted to talk to someone I knew at Berkeley or M.I.T. about this, I had to get up from the S.D.C. terminal, go over and log into the other terminal and get in touch with them.

I said, oh, man, it’s obvious what to do: If you have these three terminals, there ought to be one terminal that goes anywhere you want to go where you have interactive computing. That idea is the ARPAnet.

— Robert W. Taylor

Linking those local messaging systems over ARPANET to create inter-computer mail was one of the earliest uses considered, even before the network was up and running.

J.C.R. Licklider mentioned inter-computer mail to me in a conversation about 1968, when he asked me if I was interested in a project he had in mind, “to connect all the ARPA-funded machines together, and see what they said to each other.” He was recruiting folks for what became the Project MAC networking group. By that time, many time-sharing systems had some kind of internal mail. Discussion of linking the mail systems on various computers was one of the earliest applications proposed for the ARPANet.— Tom Van Vleck

User ?something? Host

In 1971 Ray Tomlinson was enhancing SNDMSG, the tool used to send local mail on TENEX systems. There had been discussions about how to implement a standardized form of network mail, but they were perhaps overly complex and too paper-based. Something less weighty was needed.

BBN had two TENEX systems, side-by-side, both attached to ARPANET. Ray realized he could extend SNDMSG to use an existing TENEX tool. CPYNET, that copied files from one machine to another, allowing it to send mail over the network. Sometimes you need a simple hack to demo a concept.

That was the first mail sent from one computer to another over the network.

The “@” sign was a character not used in names, and wasn’t really used for anything on TENEX, so Ray chose to use it as a separator between the user and host. It’s a happy accident that BBN used TENEX systems; if they’d had the other type of system used on ARPANET, Multics, the “@” key would have already had a reserved use – deleting the current line – and we might not have seen it used for email.

It’d be nice to have a standard protocol about now

To make network mail work between different machines, you need a way to transfer the message that’s a bit more portable than CPYNET. File Transfer Protocol (FTP) was being developed as a standard way of copying files from one machine to another. At one of the FTP development meetings, someone proposed sending mail via FTP. Someone from BBN mentioned that Ray had done something similar, using user@host addresses. A standard for email transfer began to be born.

It’s a two-way conversation

SNDMSG already used “business memo” style messages – To:, From:, Subject:, Cc:, Date: etc. – so the messages it sent looked like modern email in many respects; that format was adopted, and began to be [rfc 561]standardized.[/rfc]

At first the user interface was crude, allowing recent messages to be dumped to the users terminal or new messages to be composed. Fairly quickly tools were developed that allowed individual messages to be read or deleted.

There was still a critical element missing. That was the ability to reply to an email.

John Vittal combined and extended existing tools to create MSG, adding several new features including “Answer” – a command to automatically create a message formatted as a reply to the current one. MSG was the first integrated modern email client.

It included a command for replying to a message, similar to what is used today. My impression at the time was that, as soon as this command became widely available, e-mail use exploded. As one of MSG’s early users, I found that it permitted quick, convenient, and sustained conversations similar to the conversations we have come to expect over e-mail today.— Dave Crocker

For me the ability to create a conversation, rather than just sending a message, is the key thing that makes email such an important and successful protocol.

Who invented email?

Ray Tomlinson sent the first mail over the network, and used the “@” sign. Dave Crocker developed the [rfc 822]standard format[/rfc] for mail (and continues to develop new standards). They were both honored by the IEEE “for their key roles in the conceptualization, first implementation and standardization of networked email“.

But email wasn’t invented by a single person, or by two people, or three. There was no single unknown genius who created it, or even a significant fraction of it, despite what recent PR campaigns may have tried to convince you of.

It was a collaborative effort by many people. I was going to list some of their names here, but the list kept getting longer and I was still sure that I was missing people.

Take a look at the authors of the early email RFCs I talked about yesterday, or the names in some of the articles I relied on today, and you’ll see some of the people who created email.

EmailHistory.org – Dave Crocker – a timeline, and lots of references

Citations and notes on the development of email – David C. Walden

The Technical Development of Internet Email – Craig Partridge

A history of e-mail: Collaboration, innovation and the birth of a system – Dave Crocker

The History of Electronic Mail – Tom Van Vleck

The Evolution of ARPANET email – Ian R. Hardy

Networked E-mail – David Walden – BBN’s role

Email – Wikipedia

Email History – Livinginternet.com