Email History through RFCs

Many aspects of email are a lot older than you may think.

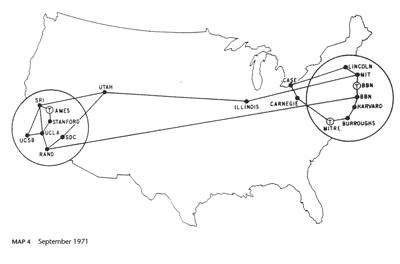

There were quite a few people in the early 1970s working out how to provide useful services using ARPANET, the network that evolved over the next 10 or 15 years into the modern Internet.

They used Requests for Comment (RFCs) to document protocol and research, much as is still done today. Here are some of the interesting milestones.

April 1971 [rfc 114]RFC 114 A File Transfer Protocol.[/rfc] One of the earliest services that was deployed so as to be useful to people, rather than a required part of the network infrastructure, was a way to transfer files from one computer to another. In the [rfc 114]earliest versions[/rfc] of the service I can find it could already append text to an existing file. This was soon used for sending short messages, initially to a remote printer from where it would be sent by internal mail, but soon also to a mailbox where they could be read online.

August 1971 [rfc 221]RFC 221 A Mail Box Protocol, Version-2[/rfc] had this prescient paragraph:

The other problem which was raised about the Mail Box Protocol was the possibility of someone accidentally or deliberately flooding the printer of a site with garbage, as there are no access or file size controls. Some thinking and discussions of this problem have yielded no simple satisfactory solutions. I would recommend initial implementations without standard special safeguards in this area. Safeguards would be a site-dependent option. Standard safeguards for the above problem can be easily added later if they really prove necessary and satisfactory ones can be agreed on.

August 1972 [rfc 385]RFC 385 Comments on the File Transfer Protocol[/rfc] formalized the use of this for electronic mail providing the command “MAIL <user>”. This let you interactively send a message to a user on a remote system identified either by their username on the remote system you connected to or by their “NIC IDENT”, the latter being a global way of identifying a person or a role mailbox. The protocol used required you to mark the end of your message with a line consisting of a single period, just the same as modern ESMTP mail.

November 1972 [rfcx 414] – uses user@host email addresses as primary contact information.

February 1973 [rfc 458]RFC 458 Mail Retrieval via FTP[/rfc] allowed a user to directly read email in a remote mailbox, a distant ancestor of modern POP and IMAP.

March 1973 [rfcx 469] and [rfcx 475] discuss the development of email from a simple remote-file-append system to a richer store-and-forward, including the first mention of “MAIL FROM” and an early mention of the “@” sign to create email addresses (adopted from Tenex SNDMSG?).

June 1973 [rfc 524]RFC 524 A Proposed Mail Protocol[/rfc]. This is a very complex, and complete, description of a mail protocol. It has the first mentions I’ve seen of delivery receipts and status notifications, but is mostly useful to understand quite how simple Simple Mail Transfer Protocol is in comparison, and the elegance of separating message delivery from message structure. [rfcx 539] responds to this, bringing up the idea of mail as a standalone protocol (rather than a subprotocol of FTP) and forwarding of email from one address to another.

September 1973 [rfc 561]RFC 561 Standardizing Network Mail Headers[/rfc]. Lots of this looks familiar – From:, Date:, Subject:! This describes the separation of email payload metadata from email routing data – though it’s described as a short-term interim solution. This will evolve into [rfcx 680], [rfcx 724], [rfcx 733], [rfcx 822], [rfcx 2822] and finally todays [rfcx 5322].

October 1973 [rfc 577]RFC 577 Mail Priority[/rfc] has the first mention of electronic junk mail I’ve seen.

July 1974 [rfc 644]RFC 644 On the Problem of Signature Authentication for Network Mail[/rfc] is an early discussion of how to be sure that email came from who it claims to be from.

November 1975 [rfc 706]RFC 706 On the Junk Mail Problem[/rfc] – Network level rejection of sources of unwanted email (the “IMP” is the router to the network).

… there is no mechanism for the Host to selectively refuse messages. This means that a Host which desires to receive some particular messages must read all messages addressed to it.

…

It would be useful for a Host to be able to decline messages from sources it believes are misbehaving or are simply annoying.

…

A Host might make use of such a facility by measuring, per source, the number of undesired messages per unit time, if this measure exceeds a threshold then the Host could issue the “refuse messages from Host X” message to the IMP.

March 1979 [rfc 753]RFC 753 Internet Message Protocol[/rfc] is a proposed binary format for mail transfer. It’s not SMTP yet, but the ideas are evolving.

August 1980 [rfc 767]RFC 767 A Structured Format for Transmission of Multi-Media Documents[/rfc] – the beginnings of MIME

September 1980 [rfc 772]RFC 772 Mail Transfer Protocol[/rfc]. This is fairly recognizable as modern SMTP.

The objective of Mail Transfer Protocol (MTP) is to transfer mail reliably and efficiently.

It will evolve through [rfcx 780], [rfcx 788], [rfcx 821] and [rfcx 2821] to become modern ESMTP in [rfcx 5321].

(Alisa Bagrii has provided a translation of this post into Russian, over at EveryCloud.)